An Interview With Seth Strand

Seth Strand grew up with a pencil in his hand. He’s from small town Iowa, and he said all he ever cared about growing up was art.

“I’ve been drawing since I can remember,” he said, noting that his high school counselor even created an art class for him at the end of high school, because he’d taken all other available options.

It wasn’t art school after graduation for Strand, however. Instead, he joined the military as an infantryman, went to basic training in January 2012, and deployed to Afghanistan in December. A few months later, on May 4, 2013, Strand said his life was forever changed.

They were on a convoy, Strand said, out picking apples off the only paved highway in the country. There had been an accident weeks before, causing a truck loaded with apples to overturn, dumping piles onto the highway. After clearing it, they made their way home. Strand was a driver in the first vehicle with Bravo team, Alpha team was in the second Vehicle, Charlie team in the third, and command in the rear vehicle. That second vehicle was struck by a 450-pound IED, which split the vehicle, throwing the front half into the field next to the highway, killing five members of Strand’s team as well as their interpreter.

Strand said he remembers the powerlessness as emergency personnel arriving and him “sitting in my seat not being able to do anything as they load the bodies up.”

“I (was) going through about every emotion you can go through,” he said. He was there for another three months, returning to the U.S. just before his 21st birthday.

Those nine months changed his life, both physically and mentally. Strand explained that he was diagnosed with PTSD after his deployment, along with having numerous physical issues.

“I’m 27 years old and I have the body of a 60-year old man at this point,” he said. “I really paid for it.”

He was honorably discharged two years later—in May 2015—and enrolled in Kansas State University for an art degree.

“When I got out of the army, I knew that I had to follow my lifelong dreams of being an artist. I had to do whatever I could to do that, to be happy.”

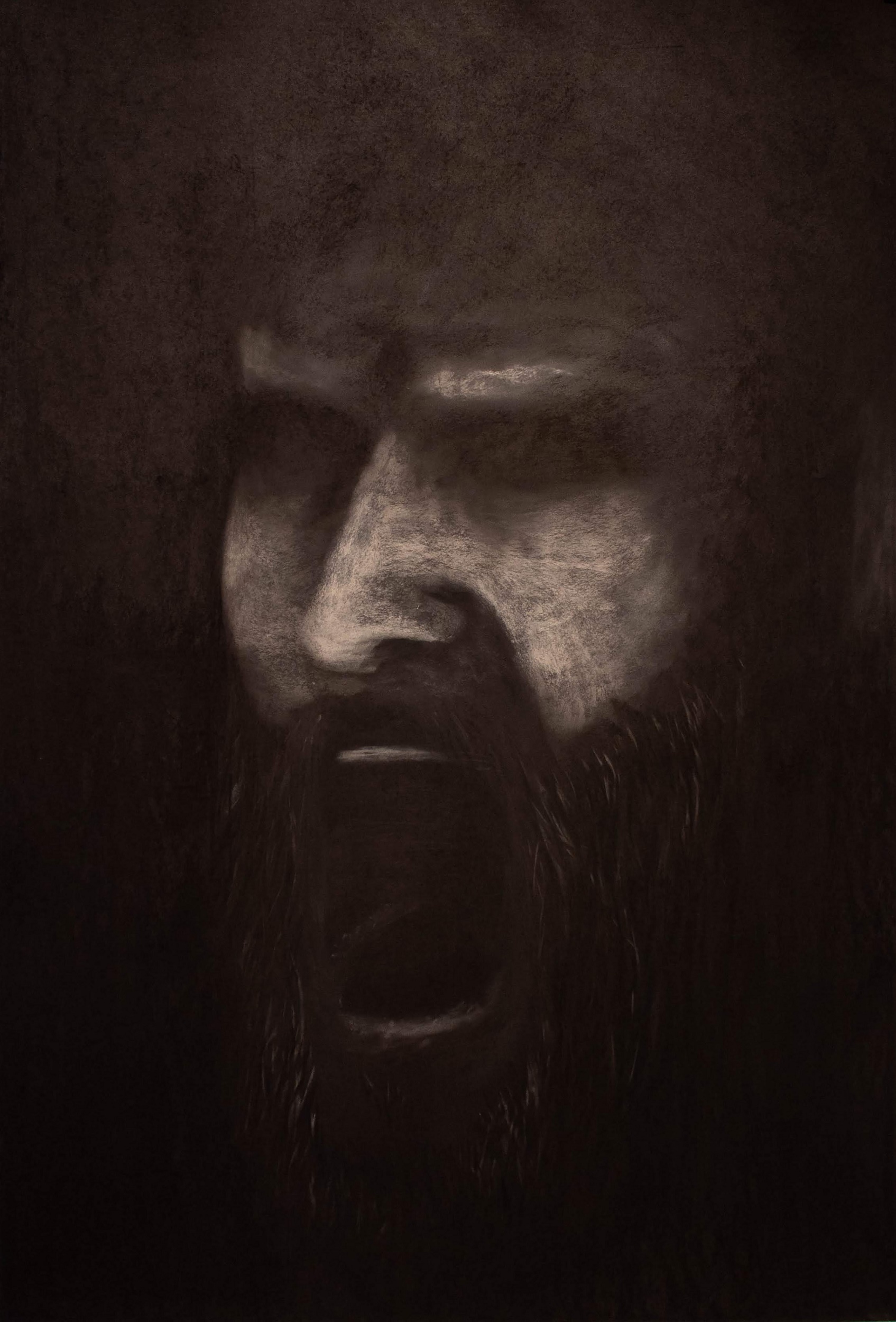

But as he explored different kinds of art—always returning to drawing and charcoal, with the occasional soft pastel—Strand said the work he felt he should do wasn’t always happy.

Eventually—and against the initial advice of his advisors—he chose to explore the events of May 4, 2013 as his final project. That work will show in Johnson County in 2021.

“The work explores what I went through that day,” he said.

He said the process of creating his work was intense as he worked to capture every emotion separately—but concurrently, just as he had experienced them. “I held a mirror and kind of put myself back into that place and put myself through those emotions again,” he said.

But Strand saw the process as a crucial part of processing his experiences. “After I got through each piece of artwork, each emotion, I felt so relieved,” he said. “I felt like that (process) was right and I think that that was extremely helpful.”

“The amount of relief that I felt when I finished, I felt like I really did it, like I got myself through it,” he said. “It really allowed me to move forward with my life. It was so important,” he explained.

Aside from his senior art show, where he showed the work, Strand said he tends to keep the pieces put away. “(Seeing it on paper) was very surreal,” he said. “It really brings me back down to my knees.”

But while looking at the work might not always be something he wants to do, Strand said he also wants his story to be told— and he hopes other veterans can break the all-too-common silence around theirs.

“I want to keep telling these stories because it’s important,” he said. “There’s a certain bravery or courageousness that it takes to pull these emotions out in front of everybody.”

He said the openness and vulnerability that can come with creating art can be an important part of healing for others, just as it has been for him.

“It wasn’t acceptable for men to be open and to cry and to be emotional,” he said. “That’s why you have 22 veteran suicides a day, just because people don’t feel like they can open themselves up.”

Strand said that opening up has been a reaction from viewers of his art as well, noting that he’s had other artists comment that they would cry just looking at his work.

“That kind of validated that I was doing it correctly, in a sense, because it is a very heart-wrenching thing to think about,” he said. “I hope that the artwork does justice to the emotion that I put into it. I hope that they see it. I guess I hope that the emotion is more prevalent than how good or bad it looks.”

Strand’s work will be featured in the Veterans’ Art Exhibit, which was postponed to summer 2021 due to COVID-19. In the meantime, you can follow his work on Instagram @seth_strand.